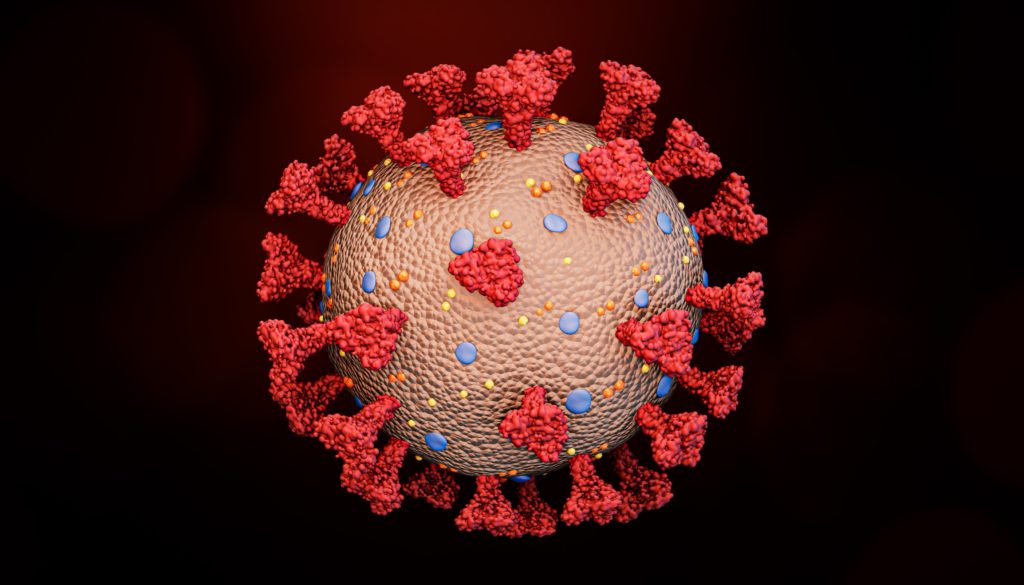

The global outbreak of COVID-19 has sparked new debate about the relationship between climate change and pandemics. In late 2019, the SARS-CoV-2 virus, better known as COVID-19, jumped from animals to humans at the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan, China. Scientists say that it is likely that the virus jumped from bats to mammals prior to this.

By November 2019, COVID-19 was circulating amongst mammals at the market. On 10 December 2019, the first case of the virus in humans was confirmed, launching a worldwide pandemic. COVID-19 is the fifth pandemic since the 1918 Spanish flu.

What does climate change have to do with pandemics?

Scientists now believe that pandemics are becoming more frequent, driven by the same global factors that are causing biodiversity loss and climate change. These factors include agricultural expansion and intensification, wildlife trade and consumption, and changes in land use. These factors all bring wildlife, livestock and people into close contact.

This provides an opportunity for animal microbes to move into people and, in cases like COVID-19, to cause global pandemics. In part, this is amplified by high population densities and increased globalisation.

Studies show that climate change is forcing species to move in the search of cooler temperatures. The destruction of habitats is also shifting animal behaviour. These changes are bringing humans and pathogen-carrying animals into unprecedented contact with each other.

Preventing global warming is crucial for many reasons. Preventing more pandemics, like COVID-19, from occurring is just one of them.

The relationship between global warming and the rise of infectious diseases

Global warming has led to a rise in infectious diseases among humans. One key reason for this is that the increase in temperatures is causing this migration of animal species towards colder areas. A study of 40,000 species worldwide found that approximately half are already on the move. Research that tracked the movement of 4,000 species over several decades found that as many as 70 per cent were migrating.

Land animals are moving polewards by 10 miles per decade on average. Likewise, marine animals are moving 45 miles per decade. Some frogs and fungi species in the Andes Mountains have climbed a quarter of a mile higher over the past 70 years. Meanwhile, in Canada, parasites have been found living under the skin of wild birds from over 950 miles southeast in Canada. This movement brings animals into contact with other species that they would not normally encounter. It creates opportunities for pathogens to move to new hosts.

Biodiversity and habitat loss

Biodiversity loss also disrupts nature and means that animals lose their homes and have to move. Agriculture and mining are primarily disrupting nature, followed by harvesting, logging, hunting and fishing. In fact, scientists have found that agricultural drivers were associated with over 25 per cent of all infectious diseases that have emerged since 1940, and over 50 per cent of zoonotic infectious diseases.

Habitat loss also leads to a loss of predators in nature. This leaves room for smaller species populations, which often carry diseases, to grow unchecked.

Climate change and pandemics

Humans

Prof Hans-Otto Poertner, head of biosciences at the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) and co-chair of the impacts chapter of the Working Group II’s contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report, has said, “Climate change shapes the biogeographical distribution of species. If, in the future, we see species moving into areas where humans are prevalent, we could see new opportunities for pandemics to evolve.”

More than 60 per cent of new infectious diseases originate in animals. The majority, approximately 70 per cent, come from wildlife. This includes Ebola, Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and HIV. The Black Death, rabies, mad cow disease and bird flu were also all passed from animals to humans.

Estimates for the number of potentially harmful viruses already in circulation amongst mammal and bird populations are as high as 1.7 million. “Any one of these could be the next ‘disease X’ – potentially even more disruptive and lethal than Covid-19.”, according to IPBES authors.

Bats

Since 1850, climate change has driven global temperatures up by 1.07°C. In the Yunnan Province of China and the bordering areas of Myanmar and Laos, conditions have become warmer and sunnier. This has led to areas of shrubs and smaller plants converting to forests, as plants and trees have grown more quickly. Bats thrive in forests, and 40 bat species have moved to the area in the past century. Their movement has also been motivated by the climate change-induced alteration in insect behaviour, one of their main food sources.

Bats are also carriers of at least 3,000 types of coronavirus. Their immune systems are tolerant of infections. This enables them to host many types of viruses without getting sick. Bats also have long life spans of up to 40 years and travel widely, around 30 miles each night. Therefore, they are prone to spreading diseases to other animals or humans. Bats are thought to be the carrier of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mosquitos

It is not just bats’ behaviour that connects climate change and pandemics.

Warmer and wetter weather is often a consequence of global warming. This alters the areas in which mosquitos and the diseases that they transmit can live. It has led to a greater risk of the transmission of various mosquito-borne viruses, such as yellow fever, dengue virus and chikungunya virus.

Chikungunya is a tropical disease. It is transmitted by the tiger mosquito. This mosquito was originally confined to tropical areas around the Indian Ocean. However, in the summer of 2007, more than 100 residents of the town of Ravenna in Italy fell ill. It was an outbreak of the chikungunya virus. By 2014, chikungunya outbreaks were occurring across all continents. Though it is not usually a fatal disease, chikungunya serves as a warning of the interlinked relationship between climate change and pandemics. If this tropical disease can become endemic throughout the world, so can more deadly infections.

What are some emerging infectious diseases and could they potentially give rise to further pandemics?

Emerging infectious diseases fall into three categories. They can be:

- Outbreaks of previously unknown diseases

- Known diseases that rapidly increase in incidence or geographic range

- Persistent infectious diseases that threaten to spiral out of control

Some examples of emerging diseases include HIV infections, SARS, Lyme disease, E.coli, hantavirus, dengue fever, West Nile virus and the Zika virus.

Emerging and reemerging infectious diseases are on the rise globally. In part, this is due to people travelling more frequently and across far greater distances in less time than ever before. It is also a side effect of living in densely populated areas. But, it is also due to humans’ growing contact with wild animals, which stems from habitat destruction and climate change migrations. As such, the risk that emerging infectious diseases could spread across human populations and cause global pandemics is a significant concern.

It has been shown that global warming is increasing the likelihood of cross-species infections. Deforestation and the conversion of wilderness to agricultural or urban landscapes also raises the likelihood of new pandemics. These acts decimate an ecosystems’ biodiversity.

Can we prevent pandemics?

While preventing pandemics is no easy task, we can reduce the risk of them by slowing down climate change and biodiversity loss.

Scientists have been warning of the dangers of increasing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere for decades. Fossil fuel companies and pro-business politicians have been ignoring their recommendations. Now, there is substantial evidence to show that global warming is leading us dangerously close to environmental catastrophe. In addition, largely thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic, the world is waking up to the threat that climate change and pandemics present.

Addressing climate change alone will not be enough to prevent pandemics. We must slow down biodiversity loss and the destruction of habitats. We must also include testing for pathogens in conservation programmes and increase healthcare provision for all people.

It is not too late to curb the worst effects of biodiversity loss, climate change and prevent future pandemics. But, this will require drastic action worldwide starting now.